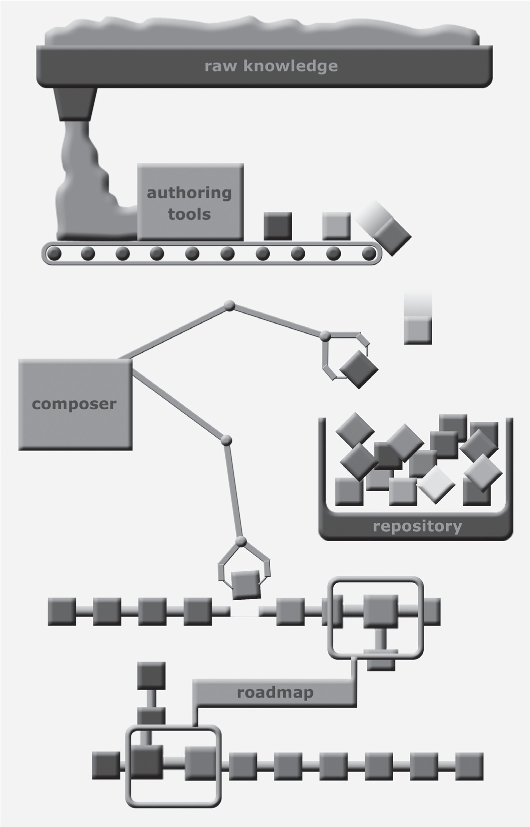

~[* The Connexions textbook as a factory. Illustration by Jenn Drummond, Ross Reedstrom, Max Starkenberg, and others, 1999-2004. Used with permission. ]~

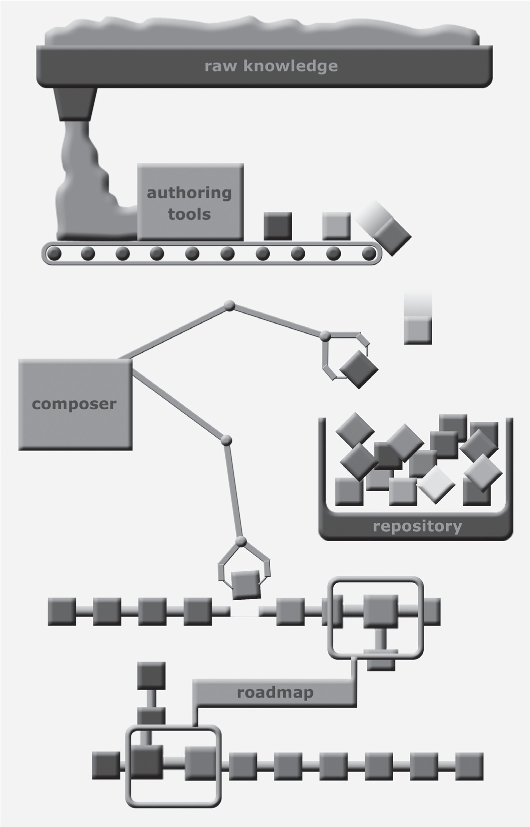

~[* The Connexions textbook as a factory. Illustration by Jenn Drummond, Ross Reedstrom, Max Starkenberg, and others, 1999-2004. Used with permission. ]~

In early 2002, after years of reading and learning about Open Source and Free Software, I finally had a chance to have dinner with famed libertarian, gun-toting, Open Source-founding impresario Eric Raymond, author of The Cathedral and the Bazaar and other amateur anthropological musings on the subject of Free Software. He had come to Houston, to Rice University, to give a talk at the behest of the Computer and Information Technology Institute (CITI). Visions of a mortal confrontation between two anthropologists-manqué filled my head. I imagined explaining point by point why his references to self-organization and evolutionary psychology were misguided, and how the long tradition of economic anthropology contradicted basically everything he had to say about gift-exchange. Alas, two things conspired against this epic, if bathetic, showdown.

First, there was the fact that (as so often happens in meetings among geeks) there was only one woman present at dinner; she was [pg 244] young, perhaps unmarried, but not a student—an interested female hacker. Raymond seated himself beside this woman, turned toward her, and with a few one-minute-long exceptions proceeded to lavish her with all of his available attention. The second reason was that I was seated next to Richard Baraniuk and Brent Hendricks. All at once, Raymond looked like the past of Free Software, arguing the same arguments, using the same rhetoric of his online publications, while Baraniuk and Hendricks looked like its future, posing questions about the transformation—the modulation—of Free Software into something surprising and new.

Baraniuk, a professor of electrical engineering and a specialist in digital signal processing, and Hendricks, an accomplished programmer, had started a project called Connexions, an “open content repository of educational materials.” Far more interesting to me than Raymond’s amateur philosophizing was this extant project to extend the ideas of Free Software to the creation of educational materials—textbooks, in particular.

Rich and Brent were, by the looks of it, equally excited to be seated next to me, perhaps because I was answering their questions, whereas Raymond was not, or perhaps because I was a new hire at Rice University, which meant we could talk seriously about collaboration. Rich and Brent (and Jan Odegard, who, as director of CITI, had organized the dinner) were keen to know what I could add to help them understand the “social” aspects of what they wanted to do with Connexions, and I, in return, was equally eager to learn how they conceptualized their Free Software-like project: what had they kept the same and what had they changed in their own experiment? Whatever they meant by “social” (and sometimes it meant ethical, sometimes legal, sometimes cultural, and so on), they were clear that there were domains of expertise in which they felt comfortable (programming, project management, teaching, and a particular kind of research in computer science and electrical engineering) and domains in which they did not (the “norms” of academic life outside their disciplines, intellectual-property law, “culture”). Although I tried to explain the nature of my own expertise in social theory, philosophy, history, and ethnographic research, the academic distinctions were far less important than the fact that I could ask detailed and pointed questions about the project, questions that indicated to them that I must have some kind of stake in the domains that they needed filled—in particular, [pg 245] around the question of whether Connexions was the same thing as Free Software, and what the implications of that might be.

Raymond courted and chattered on, then left, the event of his talk and dinner of fading significance, but over the following weeks, as I caught up with Brent and Rich, I became (surprisingly quickly) part of their novel experiment.

My nonmeeting with Raymond is an allegory of sorts: an allegory of what comes after Free Software. The excitement around that table was not so much about Free Software or Open Source, but about a certain possibility, a kind of genotypic urge of which Free Software seemed a fossil phenotype and Connexions a live one. Rich and Brent were people in the midst of figuring something out. They were engaged in modulating the practices of Free Software. By modulation I mean exploring in detail the concrete practices—the how—of Free Software in order to ask what can be changed, and what cannot, in order to maintain something (openness?) that no one can quite put his finger on. What drew me immediately to Connexions was that it was related to Free Software, not metaphorically or ideologically, but concretely, practically, and experimentally, a relationship that was more about emergence out of than it was about the reproduction of forms. But the opposition between emergence and reproduction immediately poses a question, not unlike that of the identity of species in evolution: if Free Software is no longer software, what exactly is it?

In part III I confront this question directly. Indeed, it was this question that necessitated part II, the analytic decomposition of the practices and histories of Free Software. In order to answer the question “Is Connexions Free Software?” (or vice versa) it was necessary to rethink Free Software as itself a collective, technical experiment, rather than as an expression of any ideology or culture. To answer yes, or no, however, merely begs the question “What is Free Software?” What is the cultural significance of these practices? The concept of a recursive public is meant to reveal in part the significance of both Free Software and emergent projects like Connexions; it is meant to help chart when these emergent projects branch off absolutely (cease to be public) and when they do not, by [pg 246] focusing on how they modulate the five components that give Free Software its contemporary identity.

Connexions modulates all of the components except that of the movement (there is, as of yet, no real “Free Textbook” movement, but the “Open Access” movement is a close second cousin).

Connexions emerged out of Free Software, and not, as one might expect, out of education, textbook writing, distance education, or any of those areas that are topically connected to pedagogy. That is to say, the people involved did not come to their project by attempting to deal with a problem salient to education and teaching as much as they did so through the problems raised by Free Software and the question of how those problems apply to university textbooks. Similarly, a second project, Creative Commons, also emerged out of a direct engagement with and exploration of Free Software, and not out of any legal movement or scholarly commitment to the critique of intellectual-property law or, more important, out of any desire to transform the entertainment industry. Both projects are resolutely committed to experimenting with the given practices of Free Software—to testing their limits and changing them where they can—and this is what makes them vibrant, risky, and potentially illuminating as cases of a recursive public.

While both initiatives are concerned with conventional subject areas (educational materials and cultural productions), they enter the fray orthogonally, armed with anxiety about the social and moral order in which they live, and an urge to transform it by modulating Free Software. This binds such projects across substantive domains, in that they are forced to be oppositional, not because they want to be (the movement comes last), but because they enter the domains of education and the culture industry as outsiders. They are in many ways intuitively troubled by the existing state of affairs, and their organizations, tools, legal licenses, and movements are seen as alternative imaginations of social order, especially concerning creative freedom and the continued existence of a commons of scholarly knowledge. To the extent that these projects [pg 247] remain in an orthogonal relationship, they are making a recursive public appear—something the textbook industry and the entertainment industry are, by contrast, not at all interested in doing, for obvious financial and political reasons.

I’m at dinner again. This time, a windowless hotel conference room in the basement maybe, or perhaps high up in the air. Lawyers, academics, activists, policy experts, and foundation people are semi-excitedly working their way through the hotel’s steam-table fare. I’m trying to tell a story to the assembled group—a story that I have heard Rich Baraniuk tell a hundred times—but I’m screwing it up. Rich always gets enthusiastic stares of wonder, light-bulbs going off everywhere, a subvocalized “Aha!” or a vigorous nod. I, on the other hand, am clearly making it too complicated. Faces and foreheads are squirmed up into lines of failed comprehension, people stare at the gravy-sodden food they’re soldiering through, weighing the option of taking another bite against listening to me complicate an already complicated world. I wouldn’t be doing this, except that Rich is on a plane, or in a taxi, delayed by snow or engineers or perhaps at an eponymous hotel in another city. Meanwhile, our co-organizer Laurie Racine, has somehow convinced herself that I have the childlike enthusiasm necessary to channel Rich. I’m flattered, but unconvinced. After about twenty minutes, so is she, and as I try to answer a question, she stops me and interjects, “Rich really needs to be here. He should really be telling this story.”

Miraculously, he shows up and, before he can even say hello, is conscripted into telling his story properly. I sigh in relief and pray that I’ve not done any irreparable damage and that I can go back to my role as straight man. I can let the superaltern speak for himself. The downside of participant observation is being asked to participate in what one had hoped first of all to observe. I do know the story—I have heard it a hundred times. But somehow what I hear, ears tuned to academic questions and marveling at some of the stranger claims he makes, somehow this is not the ear for enlightenment that his practiced and boyish charm delivers to those hearing it for the first time; it is instead an ear tuned to questions [pg 248] of why: why this project? Why now? And even, somewhat convolutedly, why are people so fascinated when he tells the story? How could I tell it like Rich?

Rich is an engineer, in particular, a specialist in Digital Signal Processing (DSP). DSP is the science of signals. It is in everything, says Rich: your cell phones, your cars, your CD players, all those devices. It is a mathematical discipline, but it is also an intensely practical one, and it’s connected to all kinds of neighboring fields of knowledge. It is the kind of discipline that can connect calculus, bioinformatics, physics, and music. The statistical and analytical techniques come from all sorts of research and end up in all kinds of interesting devices. So Rich often finds himself trying to teach students to make these kinds of connections—to understand that a Fourier transform is not just another chapter in calculus but a tool for manipulating signals, whether in bioinformatics or in music.

Around 1998 or 1999, Rich decided that it was time for him to write a textbook on DSP, and he went to the dean of engineering, Sidney Burris, to tell him about the idea. Burris, who is also a DSP man and longtime member of the Rice University community, said something like, “Rich, why don’t you do something useful?” By which he meant: there are a hundred DSP textbooks out there, so why do you want to write the hundred and first? Burris encouraged Rich to do something bigger, something ambitious enough to put Rice on the map. I mention this because it is important to note that even a university like Rice, with a faculty and graduate students on par with the major engineering universities of the country, perceives that it gets no respect. Burris was, and remains, an inveterate supporter of Connexions, precisely because it might put Rice “in the history books” for having invented something truly novel.

At about the same time as his idea for a textbook, Rich’s research group was switching over to Linux, and Rich was first learning about Open Source and the emergence of a fully free operating system created entirely by volunteers. It isn’t clear what Rich’s aha! moment was, other than simply when he came to an understanding that such a thing as Linux was actually possible. Nonetheless, at some point, Rich had the idea that his textbook could be an Open Source textbook, that is, a textbook created not just by him, but by DSP researchers all over the world, and made available to everyone to make use of and modify and improve as they saw fit, just like Linux. Together with Brent Hendricks, Yan David Erlich, [pg 249] and Ross Reedstrom, all of whom, as geeks, had a deep familiarity with the history and practices of Free and Open Source Software, Rich started to conceptualize a system; they started to think about modulations of different components of Free and Open Source Software. The idea of a Free Software textbook repository slowly took shape.

Thus, Connexions: an “open content repository of high-quality educational materials.” These “textbooks” very quickly evolved into something else: “modules” of content, something that has never been sharply defined, but which corresponds more or less to a small chunk of teachable information, like two or three pages in a textbook. Such modules are much easier to conceive of in sciences like mathematics or biology, in which textbooks are often multiauthored collections, finely divided into short chapters with diagrams, exercises, theorems, or programs. Modules lend themselves much less well to a model of humanities or social-science scholarship based in reading texts, discussion, critique, and comparison—and this bias is a clear reflection of what Brent, Ross, and Rich knew best in terms of teaching and writing. Indeed, the project’s frequent recourse to the image of an assembly-line model of knowledge production often confirms the worst fears of humanists and educators when they first encounter Connexions. The image suggests that knowledge comes in prepackaged and colorfully branded tidbits for the delectation of undergrads, rather than characterizing knowledge as a state of being or as a process.

The factory image (figure 7) is a bit misleading. Rich’s and Brent’s imaginations are in fact much broader, which shows whenever they demo the project, or give a talk, or chat at a party about it. Part of my failure to communicate excitement when I tell the story of Connexions is that I skip the examples, which is where Rich starts: what if, he says, you are a student taking Calculus 101 and, at the same time, Intro to Signals and Systems—no one is going to explain to you how Fourier transforms form a bridge, or connection, between them. “Our brains aren’t organized in linear, chapter-by-chapter ways,” Rich always says, “so why are our textbooks?” How can we give students a way to see the connection between statistics and genetics, between architecture and biology, between intellectual-property law and chemical engineering? Rich is always looking for new examples: a music class for kids that uses information from physics, or vice versa, for instance. Rich’s great hope is that the [pg 250] [pg 251] more modules there are in the Connexions commons, the more fantastic and fascinating might be the possibilities for such novel—and natural—connections.

~[* The Connexions textbook as a factory. Illustration by Jenn Drummond, Ross Reedstrom, Max Starkenberg, and others, 1999-2004. Used with permission. ]~

~[* The Connexions textbook as a factory. Illustration by Jenn Drummond, Ross Reedstrom, Max Starkenberg, and others, 1999-2004. Used with permission. ]~

Free Software—and, in particular, Open Source in the guise of “self-organizing” distributed systems of coordination—provide a particular promise of meeting the challenges of teaching and learning that Rich thinks we face. Rich’s commitment is not to a certain kind of pedagogical practice, but to the “social” or “community” benefits of thousands of people working “together” on a textbook. Indeed, Connexions did not emerge out of education or educational technology; it was not aligned with any particular theory of learning (though Rich eventually developed a rhetoric of linked, networked, connected knowledge—hence the name Connexions—that he uses often to sell the project). There is no school of education at Rice, nor a particular constituency for such a project (teacher-training programs, say, or administrative requirements for online education). What makes Rich’s sell even harder is that the project emerged at about the same time as the high-profile failure of dotcom bubble-fueled schemes to expand university education into online education, distance education, and other systems of expanding the paying student body without actually inviting them onto campus. The largest of these failed experiments by far was the project at Columbia, which had reached the stage of implementation at the time the bubble burst in 2000.

Thus, Rich styled Connexions as more than just a factory of knowledge—it would be a community or culture developing richly associative and novel kinds of textbooks—and as much more than just distance education. Indeed, Connexions was not the only such project busy differentiating itself from the perceived dangers of distance education. In April 2001 MIT had announced that it would make the content of all of its courses available for free online in a project strategically called OpenCourseWare (OCW). Such news could only bring attention to MIT, which explicitly positioned the announcement as a kind of final death blow to the idea of distance education, by saying that what students pay $35,000 and up for per year is not “knowledge”—which is free—but the experience of being at MIT. The announcement created pure profit from the perspective of MIT’s reputation as a generator and disseminator of scientific knowledge, but the project did not emerge directly out of an interest in mimicking the success of Open Source. That angle was [pg 252] provided ultimately by the computer-science professor Hal Abelson, whose deep understanding of the history and growth of Free Software came from his direct involvement in it as a long-standing member of the computer-science community at MIT. OCW emerged most proximately from the strange result of a committee report, commissioned by the provost, on how MIT should position itself in the “distance/e-learning” field. The surprising response: don’t do it, give the content away and add value to the campus teaching and research experience instead.

OCW, Connexions, and distance learning, therefore, while all ostensibly interested in combining education with the networks and software, emerged out of different demands and different places. While the profit-driven demand of distance learning fueled many attempts around the country, it stalled in the case of OCW, largely because the final MIT Council on Educational Technology report that recommended OCW was issued at the same time as the first plunge in the stock market (April 2000). Such issues were not a core factor in the development of Connexions, which is not to say that the problems of funding and sustainability have not always been important concerns, only that genesis of the project was not at the administrative level or due to concerns about distance education. For Rich, Brent, and Ross the core commitment was to openness and to the success of Open Source as an experiment with massive, distributed, Internet-based, collaborative production of software—their commitment to this has been, from the beginning, completely and adamantly unwavering. Neverthless, the project has involved modulations of the core features of Free Software. Such modulations depend, to a certain extent, on being a project that emerges out of the ideas and practices of Free Software, rather than, as in the case of OCW, one founded as a result of conflicting goals (profit and academic freedom) and resulting in a strategic use of public relations to increase the symbolic power of the university over its fiscal growth.

When Rich recounts the story of Connexions, though, he doesn’t mention any of this background. Instead, like a good storyteller, he waits for the questions to pose themselves and lets his demonstration answer them. Usually someone asks, “How is Connexions different from OCW?” And, every time, Rich says something similar: Connexions is about “communities,” about changing the way scholars collaborate and create knowledge, whereas OCW is simply [pg 253] an attempt to transfer existing courses to a Web format in order to make the content of those courses widely available. Connexions is a radical experiment in the collaborative creation of educational materials, one that builds on the insights of Open Source and that actually encompasses the OCW project. In retrospective terms, it is clear that OCW was interested only in modulating the meaning of source code and the legal license, whereas Connexions seeks also to modulate the practice of coordination, with respect to academic textbooks.

Rich’s story of the origin of Connexions usually segues into a demonstration of the system, in which he outlines the various technical, legal, and educational concepts that distinguish it. Connexions uses a standardized document format, the eXtensible Mark-up Language (XML), and a Creative Commons copyright license on every module; the Creative Commons license allows people not only to copy and distribute the information but to modify it and even to use it for commercial gain (an issue that causes repeated discussion among the team members). The material ranges from detailed explanations of DSP concepts (naturally) to K-12 music education (the most popular set of modules). Some contributors have added entire courses; others have created a few modules here and there. Contributors can set up workgroups to manage the creation of modules, and they can invite other users to join. Connexions uses a version-control system so that all of the changes are recorded; thus, if a module used in one class is changed, the person using it for another class can continue to use the older version if they wish. The number of detailed and clever solutions embodied in the system never ceases to thoroughly impress anyone who takes the time to look at it.

But what always animates people is the idea of random and flexible connection, the idea that a textbook author might be able to build on the work of hundreds of others who have already contributed, to create new classes, new modules, and creative connections between them, or surprising juxtapositions—from the biologist teaching a class on bioinformatics who needs to remind students of certain parts of calculus without requiring a whole course; to the architect who wants a studio to study biological form, not necessarily in order to do experiments in biology, but to understand buildings differently; to the music teacher who wants students to understand just enough physics to get the concepts of pitch and [pg 254] timbre; to or the physicist who needs a concrete example for the explanation of waves and oscillation.

The idea of such radical recombinations is shocking for some (more often for humanities and social-science scholars, rather than scientists or engineers, for reasons that clearly have to do with an ideology of authentic and individualized creative ability). The questions that result—regarding copyright, plagiarism, control, unauthorized use, misuse, misconstrual, misreading, defamation, and so on—generally emerge with surprising force and speed. If Rich were trying to sell a version of “distance learning,” skepticism and suspicion would quickly overwhelm the project; but as it is, Connexions inverts almost all of the expectations people have developed about textbooks, classroom practice, collaboration, and copyright. More often than not people leave the discussion converted—no doubt helped along by Rich’s storytelling gift.

Connexions surprises people for some of the same reasons as Free Software surprises people, emerging, as it does, directly out of the same practices and the same components. Free Software provides a template made up of the five components: shared source code, a concept of openness, copyleft licenses, forms of coordination, and a movement or ideology. Connexions starts with the idea of modulating a shared “source code,” one that is not software, but educational textbook modules that academics will share, port, and fork. The experiment that results has implications for the other four components as well. The implications lead to new questions, new constraints, and new ideas.

The modulation of source code introduces a specific and potentially confusing difference from Free Software projects: Connexions is both a conventional Free Software project and an unconventional experiment based on Free Software. There is, of course, plenty of normal source code, that is, a number of software components that need to be combined in order to allow the creation of digital documents (the modules) and to display, store, transmit, archive, and measure the creation of modules. The creation and management of this software is expected to function more or less like all Free Software projects: it is licensed using Free Software licenses, it is [pg 255] built on open standards of various kinds, and it is set up to take contributions from other users and developers. The software system for managing modules is itself built on a variety of other Free Software components (and a commitment to using only Free Software). Connexions has created various components, which are either released like conventional Free Software or contributed to another Free Software project. The economy of contribution and release is a complex one; issues of support and maintenance, as well as of reputation and recognition, figure into each decision. Others are invited to contribute, just as they are invited to contribute to any Free Software project.

At the same time, there is “content,” the ubiquitous term for digital creations that are not software. The creation of content modules, on the other hand (which the software system makes technically possible), is intended to function like a Free Software project, in which, for instance, a group of engineering professors might get together to collaborate on pieces of a textbook on DSP. The Connexions project does not encompass or initiate such collaborations, but, rather, proceeds from the assumption that such activity is already happening and that Connexions can provide a kind of alternative platform—an alternative infrastructure even—which textbook-writing academics can make use of instead of the current infrastructure of publishing. The current infrastructure and technical model of textbook writing, this implies, is one that both prevents people from taking advantage of the Open Source model of collaborative development and makes academic work “non-free.” The shared objects of content are not source code that can be compiled, like source code in C, but documents marked up with XML and filled with “educational” content, then “displayed” either on paper or onscreen.

The modulated meaning of source code creates all kinds of new questions—specifically with respect to the other four components. In terms of openness, for instance, Connexions modulates this component very little; most of the actors involved are devoted to the ideals of open systems and open standards, insofar as it is a Free Software project of a conventional type. It builds on UNIX (Linux) and the Internet, and the project leaders maintain a nearly fanatical devotion to openness at every level: applications, programming languages, standards, protocols, mark-up languages, interface tools. Every place where there is an open (as opposed to a [pg 256] proprietary) solution—that choice trumps all others (with one noteworthy exception).

With respect to content, the devotion to openness is nearly identical, because conventional textbook publishers “lock in” customers (students) through the creation of new editions and useless “enhanced” content, which jacks up prices and makes it difficult for educators to customize their own courses. “Openness” in this sense trades on the same reasoning as it did in the 1980s: the most important aspect of the project is the information people create, and any proprietary system locks up content and prevents people from taking it elsewhere or using it in a different context.

Indeed, so firm is the commitment to openness that Rich and Brent often say something like, “If we are successful, we will disappear.” They do not want to become a famous online textbook publisher; they want to become a famous publishing infrastructure. Being radically open means that any other competitor can use your system—but it means they are using your system, and this is the goal. Being open means not only sharing the “source code” (content and modules), but devising ways to ensure the perpetual openness of that content, that is, to create a recursive public devoted to the maintenance and modifiability of the medium or infrastructure by which it communicates. Openness trumps “sustainability” (i.e., the self-perpetuation of the financial feasibility of a particular organization), and where it fails to, the commitment to openness has been compromised.

The commitment to openness and the modulation of the meaning of source code thus create implications for the meaning of Free Software licenses: do such licenses cover this kind of content? Are new licenses necessary? What should they look like? Connexions was by no means the first project to stimulate questions about the applicability of Free Software licenses to texts and documents. In the case of EMACS and the GPL, for example, Richard Stallman had faced the problem of licensing the manual at the same time as the source code for the editor. Indeed, such issues would ultimately result in a GNU Free Documentation License intended narrowly to [pg 257] cover software manuals. Stallman, due to his concern, had clashed during the 1990s with Tim O’Reilly, publisher and head of O’Reilly Press, which had long produced books and manuals for Free Software programs. O’Reilly argued that the principles reflected in Free Software licenses should not be applied to instructional books, because such books provided a service, a way for more people to learn how to use Free Software, and in turn created a larger audience. Stallman argued the opposite: manuals, just like the software they served, needed to be freely modifiable to remain useful.

By the late 1990s, after Free Software and Open Source had been splashed across the headlines of the mainstream media, a number of attempts to create licenses modeled on Free Software, but applicable to other things, were under way. One of the earliest and most general was the Open Content License, written by the educational-technology researcher David Wiley. Wiley’s license was intended for use on any kind of content. Content could include text, digital photos, movies, music, and so on. Such a license raises new issues. For example, can one designate some parts of a text as “invariant” in order to prevent them from being changed, while allowing other parts of the text to be changed (the model eventually adopted by the GNU Free Documentation License)? What might the relationship between the “original” and the modified version be? Can one expect the original author to simply incorporate suggested changes? What kinds of forking are possible? Where do the “moral rights” of an author come into play (regarding the “integrity” of a work)?

At the same time, the modulation of source code to include academic textbooks has extremely complex implications for the meaning and context of coordination: scholars do not write textbooks like programmers write code, so should they coordinate in the same ways? Coordination of a textbook or a course in Connexions requires novel experiments in textbook writing. Does it lend itself to academic styles of work, and in which disciplines, for what kinds of projects? In order to cash in on the promise of distributed, collaborative creation, it would be necessary to find ways to coordinate scholars.

So, when Rich and Brent recognized in me, at dinner, someone who might know how to think about these issues, they were acknowledging that the experiment they had started had created a certain turbulence in their understanding of Free Software and, [pg 258] in turn, a need to examine the kinds of legal, cultural, and social practices that would be at stake.

I’m standing in a parking lot in 100 degree heat and 90 percent humidity. It is spring in Houston. I am looking for my car, and I cannot find it. James Boyle, author of Shamans, Software, and Spleens and distinguished professor of law at Duke University, is standing near me, staring at me, wearing a wool suit, sweating and watching me search for my car under the blazing sun. His look says simply, “If I don’t disembowel you with my Palm Pilot stylus, I am going to relish telling this humiliating story to your friends at every opportunity I can.” Boyle is a patient man, with the kind of arch Scottish humor that can make you feel like his best friend, even as his stories of the folly of man unfold with perfect comic pitch and turn out to be about you. Having laughed my way through many an uproarious tale of the foibles of my fellow creatures, I am aware that I have just taken a seat among them in Boyle’s theater of human weakness. I repeatedly press the panic button on my key chain, in the hopes that I am near enough to my car that it will erupt in a frenzy of honking and flashing that will end the humiliation.

The day had started well. Boyle had folded himself into my Volkswagen (he is tall), and we had driven to campus, parked the car in what no doubt felt like a memorable space at 9 A.M., and happily gone to the scheduled meeting—only to find that it had been mistakenly scheduled for the following day. Not my fault, though now, certainly, my problem. The ostensible purpose of Boyle’s visit was to meet the Connexions team and learn about what they were doing. Boyle had proposed the visit himself, as he was planning to pass through Houston anyway. I had intended to pester him with questions about the politics and possibilities of licensing the content in Connexions and with comparisons to MIT’s OCW and other such commons projects that Boyle knew of.

Instead of attending the meeting, I took him back to my office, where I learned more about why he was interested in Connexions. Boyle’s interest was not entirely altruistic (nor was it designed to spend valuable quarter hours standing in a scorched parking lot as I looked for my subcompact car). What interested Boyle was finding [pg 259] a constituency of potential users for Creative Commons, the nonprofit organization he was establishing with Larry Lessig, Hal Abelson, Michael Carroll, Eric Eldred, and others—largely because he recognized the need for a ready constituency in order to make Creative Commons work. The constituency was needed both to give the project legitimacy and to allow its founders to understand what exactly was needed, legally speaking, for the creation of a whole new set of Free Software-like licenses.

Creative Commons, as an organization and as a movement, had been building for several years. In some ways, Creative Commons represented a simple modulation of the Free Software license: a broadening of the license’s concept to cover other types of content. But the impetus behind it was not simply a desire to copy and extend Free Software. Rather, all of the people involved in Creative Commons were those who had been troubling issues of intellectual property, information technology, and notions of commons, public domains, and freedom of information for many years. Boyle had made his name with a book on the construction of the information society by its legal (especially intellectual property) structures. Eldred was a publisher of public-domain works and the lead plaintiff in a court case that went to the Supreme Court in 2002 to determine whether the recent extension of copyright term limits was constitutional. Abelson was a computer scientist with an active interest in issues of privacy, freedom, and law “on the electronic frontier.” And Larry Lessig was originally interested in constitutional law, a clerk for Judge Richard Posner, and a self-styled cyberlaw scholar, who was, during the 1990s, a driving force for the explosion of interest in cyberlaw, much of it carried out at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University.

With the exception of Abelson—who, in addition to being a famous computer scientist, worked for years in the same building that Richard Stallman camped out in and chaired the committee that wrote the report recommending OCW—none of the members of Creative Commons cut their teeth on Free Software projects (they were lawyers and activists, primarily) and yet the emergence of Open Source into the public limelight in 1998 was an event that made more or less instant and intuitive sense to all of them. During this time, Lessig and members of the Berkman Center began an “open law” project designed to mimic the Internet-based collaboration of the Open Source project among lawyers who might want to [pg 260] contribute to the Eldred case. Creative Commons was thus built as much on a commitment to a notion of collaborative creation—the use of the Internet especially—but more generally on the ability of individuals to work together to create new things, and especially to coordinate the creation of these things by the use of novel licensing agreements.

Creative Commons provided more than licenses, though. It was part of a social imaginary of a moral and technical order that extended beyond software to include creation of all kinds; notions of technical and moral freedom to make use of one’s own “culture” became more and more prominent as Larry Lessig became more and more involved in struggles with the entertainment industry over the “control of culture.” But for Lessig, Creative Commons was a fall-back option; the direct route to a transformation of the legal structure of intellectual property was through the Eldred case, a case that built huge momentum throughout 2001 and 2002, was granted cert by the Supreme Court, and was heard in October of 2002. One of the things that made the case remarkable was the series of strange bedfellows it produced; among the economists and lawyers supporting the repeal of the 1998 “Sonny Bono” Copyright Term Extension Act were the arch free-marketeers and Nobel Prize winners Milton Friedman, James Buchanan, Kenneth Arrow, Ronald Coase, and George Akerlof. As Boyle pointed out in print, conservatives and liberals and libertarians all have reasons to be in favor of scaling back copyright expansion.

Creative Commons was thus a back-door approach: if the laws could not be changed, then people should be given the tools they needed to work around those laws. Understanding how Creative Commons was conceived requires seeing it as a modulation of both the notion of “source code” and the modulation of “copyright licenses.” But the modulations take place in that context of a changing legal system that was so unfamiliar to Stallman and his EMACS users, a legal system responding to new forms of software, networks, and devices. For instance, the changes to the Copyright Act of 1976 created an unintended effect that Creative Commons would ultimately seize on. By eliminating the requirement to register copyrighted works (essentially granting copyright as soon as the [pg 261] work is “fixed in a tangible medium”), the copyright law created a situation wherein there was no explicit way in which a work could be intentionally placed in the public domain. Practically speaking an author could declare that a work was in the public domain, but legally speaking the risk would be borne entirely by the person who sought to make use of that work: to copy it, transform it, sell it, and so on. With the explosion of interest in the Internet, the problem ramified exponentially; it became impossible to know whether someone who had placed a text, an image, a song, or a video online intended for others to make use of it—even if the author explicitly declared it “in the public domain.” Creative Commons licenses were thus conceived and rhetorically positioned as tools for making explicit exactly what uses could be made of a specific work. They protected the rights of people who sought to make use of “culture” (i.e., materials and ideas and works they had not authored), an approach that Lessig often summed up by saying, “Culture always builds on the past.”

The background to and context of the emergence of Creative Commons was of course much more complicated and fraught. Concerns ranged from the plights of university libraries with regard to high-priced journals, to the problem of documentary filmmakers unable to afford, or even find the owners of, rights to use images or snippets in films, to the high-profile fights over online music trading, Napster, and the RIAA. Over the course of four years, Lessig and the other founders of Creative Commons would address all of these issues in books, in countless talks and presentations and conferences around the world, online and off, among audiences ranging from software developers to entrepreneurs to musicians to bloggers to scientists.

Often, the argument for Creative Commons draws heavily on the concept of culture besieged by the content industries. A story which Lessig enjoys telling—one that I heard on several occasions when I saw him speak at conferences—was that of Mickey Mouse. An interesting, quasi-conspiratorial feature of the twentieth-century expansion of intellectual-property law is that term limits seem to have been extended right around the time Mickey Mouse was about to become public property. True or not, the point Lessig likes to make is that the Mouse is not the de novo creation of the mind of Walt Disney that intellectual-property law likes to pretend it is, but built on the past of culture, in particular, on Steamboat Willie, [pg 262] Charlie Chaplin, Krazy Kat, and other such characters, some as inspiration, some as explicit material. The greatness in Disney’s creation comes not from the mind of Disney, but from the culture from which it emerged. Lessig will often illustrate this in videos and images interspersed with black-typewriter-font-bestrewn slides and a machine-gun style that makes you think he’s either a beat-poet manqué or running for office, or maybe both.

Other examples of intellectual-property issues fill the books and talks of Creative Commons advocates, stories of blocked innovation, stifled creativity, and—the scariest point of all (at least for economist-lawyers)—inefficiency due to over-expansive intellectual-property laws and overzealous corporate lawyer-hordes.

On that hot May day in 2002, however, Creative Commons was still under development. Later in the day, Boyle did get a chance to meet with the Connexions project team members. The Connexions team had already realized that in pursuing an experimental project in which Free Software was used as a template they created a need for new kinds of licenses. They had already approached the Rice University legal counsel, who, though well-meaning, were not grounded at all in a deep understanding of Free Software and were thus naturally suspicious of it. Boyle’s presence and his detailed questions about the project were like a revelation—a revelation that there were already people out there thinking about the very problem the Connexions team faced and that the team would not need to solve the problem themselves or make the Rice University legal counsel write new open-content licenses. What Boyle offered was the possibility for Connexions, as well as for myself as intermediary, to be involved in the detailed planning and license writing that was under way at Creative Commons. At the same time, it gave Creative Commons an extremely willing “early-adopter” for the license, and one from an important corner of the world: scholarly research and teaching.

The workshop I organized in August 2002 was intended to allow Creative Commons, Connexions, and MIT’s OCW project to try to articulate what each might want from the other. It was clear what Creative Commons wanted: to convince as many people as possible to use their licenses. But what Connexions and OCW might have wanted, from each other as well as from Creative Commons, was less clear. Given the different goals and trajectories of the two projects, their needs for the licenses differed in substantial ways—enough so that the very idea of using the same license was, at least temporarily, rendered impossible by MIT. While OCW was primarily concerned about obtaining permissions to place existing copyrighted work on the Web, Connexions was more concerned about ensuring that new work remain available and modifiable.

In retrospect, this workshop clarified the novel questions and problems that emerged from the process of modulating the components of Free Software for different domains, different kinds of content, and different practices of collaboration and sharing. Since then, my own involvement in this activity has been aimed at resolving some of these issues in accordance with an imagination of openness, an imagination of social order, that I had learned from my long experience with geeks, and not from my putative expertise as an anthropologist or a science-studies scholar. The fiction that I had at first adopted—that I was bringing scholarly knowledge to the table—became harder and harder to maintain the more I realized that it was my understanding of Free Software, gained through ongoing years of ethnographic apprenticeship, that was driving my involvement.

Indeed, the research I describe here was just barely undertaken as a research project. I could not have conceived of it as a fundable activity in advance of discovering it; I could not have imagined the course of events in any of the necessary detail to write a proper proposal for research. Instead, it was an outgrowth of thinking and [pg 264] participating that was already under way, participation that was driven largely by intuition and a feeling for the problem represented by Free Software. I wanted to help figure something out. I wanted to see how “figuring out” happens. While I could have organized a fundable research project in which I picked a mature Free Software project, articulated a number of questions, and spent time answering them among this group, such a project would not have answered the questions I was trying to form at the time: what is happening to Free Software as it spreads beyond the world of hackers and software? How is it being modulated? What kinds of limits are breached when software is no longer the central component? What other domains of thought and practice were or are “readied” to receive and understand Free Software and its implications?

My experience—my participant-observation—with Creative Commons was therefore primarily done as an intermediary between the Connexions project (and, by implication, similar projects under way elsewhere) and Creative Commons with respect to the writing of licenses. In many ways this detailed, specific practice was the most challenging and illuminating aspect of my participation, but in retrospect it was something of a red herring. It was not only the modulation of the meaning of source code and of legal licenses that differentiated these projects, but, more important, the meaning of collaboration, reuse, coordination, and the cultural practice of sharing and building on knowledge that posed the trickiest of the problems.

My contact at Creative Commons was not James Boyle or Larry Lessig, but Glenn Otis Brown, the executive director of that organization (as of summer 2002). I first met Glenn over the phone, as I tried to explain to him what Connexions was about and why he should join us in Houston in August to discuss licensing issues related to scholarly material. Convincing him to come to Texas was an easier sell than explaining Connexions (given my penchant for complicating it unnecessarily), as Glenn was an Austin native who had been educated at the University of Texas before heading off to Harvard Law School and its corrupting influence at the hands of Lessig, Charlie Nesson, and John Perry Barlow.

Glenn galvanized the project. With his background as a lawyer, and especially his keen interest in intellectual-property law, and his long-standing love of music of all kinds Glenn lent incredible enthusiasm to his work. Prior to joining Creative Commons, he had [pg 265] clerked for the Hon. Stanley Marcus on the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in Miami, where he worked on the so-called Wind Done Gone case.

A New York Times story describes how the band the White Stripes had allowed Steven McDonald, the bassist from Redd Kross, to lay a bass track onto the songs that made up the album White Blood Cells. In a line that would eventually become a kind of mantra for Creative Commons, the article stated: “Mr. McDonald began putting these copyrighted songs online without permission from the White Stripes or their record label; during the project, he bumped into Jack White, who gave him spoken assent to continue. It can be that easy when you skip the intermediaries.”

Glenn told the story with obvious and animated enthusiasm, ending with the assertion that the White Stripes didn’t have to give up all their rights to do this, but they didn’t have to keep them all either; instead of “All Rights Reserved,” he suggested, they could say “Some Rights Reserved.” The story not only manages to capture the message and aims of Creative Commons, but is also a nice indication of the kind of dual role that Glenn played, first as a lawyer, and second as a kind of marketing genius and message man. The possibility of there being more than a handful of people like Glenn around was not lost on anyone, and his ability to switch between the language of law and that of nonprofit populist marketing was phenomenal.

At the workshop, participants had a chance to hash out a number of different issues related to the creation of licenses that would be appropriate to scholarly content: questions of attribution and commercial use, modification and warranty; differences between federal copyright law concerning licenses and state law concerning commercial contracts. The starting point for most people was Free Software, but this was not the only starting point. There were at least two other broad threads that fed into the discussion and into the general understanding of the state of affairs facing projects like [pg 266] Connexions or OCW. The first thread was that of digital libraries, hypertext, human-computer interaction research, and educational technology. These disciplines and projects often make common reference to two pioneers, Douglas Englebart and Theodore Nelson, and more proximately to things like Apple’s HyperCard program and a variety of experiments in personal academic computing. The debates and history that lead up to the possibility of Connexions are complex and detailed, but they generally lack attention to legal detail. With the exception of a handful of people in library and information science who have made “digital” copyright into a subspecialty, few such projects, over the last twenty-five years, have made the effort to understand, much less incorporate, issues of intellectual property into their purview.

The other thread combines a number of more scholarly interests that come out of the disciplines of economics and legal theory: institutional economics, critical legal realism, law and economics—these are the scholastic designations. Boyle and Lessig, for example, are both academics; Boyle does not practice law, and Lessig has tried few cases. Nonetheless, they are both inheritors of a legal and philosophical pragmatism in which value is measured by the transformation of policy and politics, not by the mere extension or specification of conceptual issues. Although both have penned a large number of complicated theoretical articles (and Boyle is well known in several academic fields for his book Shamans, Software, and Spleens and his work on authorship and the law), neither, I suspect, would ever sacrifice the chance to make a set of concrete changes in legal or political practice given the choice. This point was driven home for me in a conversation I had with Boyle and others at dinner on the night of the launch of Creative Commons, in December 2002. During that conversation, Boyle said something to the effect of, “We actually made something; we didn’t just sit around writing articles and talking about the dangers that face us—we made something.” He was referring as much to the organization as to the legal licenses they had created, and in this sense Boyle qualifies very much as a polymathic geek whose understanding of technology is that it is an intervention into an already constituted state of affairs, one that demonstrates its value by being created and installed, not by being assessed in the court of scholarly opinions. [pg 267]

Similarly, Lessig’s approach to writing and speaking is unabashedly aimed at transforming the way people approach intellectual-property law and, even more generally, the way they understand the relationship between their rights and their culture.

Informing both thinkers is a somewhat heterodox economic consensus drawn primarily from institutional economics, which is routinely used to make policy arguments about the efficacy or efficiency of the intellectual-property system. Both are also informed by an emerging consensus on treating the public domain in the same manner in which environmentalists treated the environment in the 1960s.

All of these threads form the weft of the experiment to modulate the components of Free Software to create different licenses that cover a broader range of objects and that deal with people and organizations that are not software developers. Rather than attempt to carry on arguments at the level of theory, however, my aim in participating was to see how and what was argued in practice by the people constructing these experiments, to observe what constraints, arguments, surprises, or bafflements emerged in the course of thinking through the creation of both new licenses and a new form of authorship of scholarly material. Like those who study “science in action” or the distinction between “law on the books” and “law in action,” I sought to observe the realities of a practice [pg 268] heavily determined by textual and epistemological frameworks of various sorts.

In my years with Connexions I eventually came to see it as something in between a natural experiment and a thought experiment: it was conducted in the open, and it invited participation from working scholars and teachers (a natural experiment, in that it was not a closed, scholarly endeavor aimed at establishing specific results, but an essentially unbounded, functioning system that people could and would come to depend on), and yet it proceeded by making a series of strategic guesses (a thought experiment) about three related things: (1) what it is (and will be) possible to do technically; (2) what it is (and will be) possible to do legally; and (3) what scholars and educators have done and now do in the normal course of their activities.

At the same time, this experiment gave shape to certain legal questions that I channeled in the direction of Creative Commons, issues that ranged from technical questions about the structure of digital documents, requirements of attribution, and URLs to questions about moral rights, rights of disavowal, and the meaning of “modification.” The story of the interplay between Connexions and Creative Commons was, for me, a lesson in a particular mode of legal thinking which has been described in more scholarly terms as the difference between the Roman or, more proximately, the Napoleonic tradition of legal rationalism and the Anglo-American common-law tradition.

Copyright: 2008 Duke University Press

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞

Designed by C. H. Westmoreland

Typeset in Charis (an Open Source font) by Achorn International

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data and republication acknowledgments appear on the last printed pages of this book.

License: Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike License, available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or by mail from Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, Calif. 94305, U.S.A. "NonCommercial" as defined in this license specifically excludes any sale of this work or any portion thereof for money, even if sale does not result in a profit by the seller or if the sale is by a 501(c)(3) nonprofit or NGO.

Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Advanced Collaboratory), which provided funds to help support the electronic interface of this book.

Two Bits is accessible on the Web at twobits.net.

≅ SiSU Spine ፨ (object numbering & object search)

(web 1993, object numbering 1997, object search 2002 ...) 2024